Copyright 1999 The New York Times Company

The New York Times Magazine

July 11, 1999, Sunday

SECTION: New York Times Magazine

LENGTH: 5017 words

HEADLINE: What's a Record Exec To Do With Aimee Mann?

BYLINE: By JONATHAN VAN METER

What's a Record Exec To Do With Aimee Mann?

Critics loved her, but she couldn't remake herself as a 90's pop star. Now, with the industry in turmoil, she may not have to.

I should be riding on the float in the hit parade/instead of sitting on the curb behind the barricade/another verse in the doormat serenade.

-- "Put Me on Top," Aimee MannJuly 1999: Aimee Mann can't sit around these days waiting to hear what the record-label executives think of her new album. She is far too busy doing things for herself -- choosing press photos, writing her own bio, running to Fed Ex and, literally, licking stamps. But things weren't always this way.

July 1998: Aimee Mann is holed up for the fourth day in a row in the windowless, hyper-air-conditioned bunker that is Mad Dog Studios in Burbank, Calif., recording two new songs for her third solo album, trying her best to create some magic. Outside, the sun is ridiculously bright, the heat stifling, the whir of traffic numbing. Adding to the unreal out-of-time feeling that 10-hour days in a dimly lighted, soundproof room can produce is the fact that the singers Sheena Easton and Jeffrey Osborne are in the next studio shooting a Christmas video.

Mann is here today because shortly after she delivered seven new songs to Geffen Records, she was told by her manager, Michael Hausman, that the A&R executives "didn't hear a single." A few days after she got the bad news, she said, more resigned than angry: "There's never a single unless you're earmarked for greatness in the first place. I wish it would be called for what it is. Like, 'These are good songs, but they're just not grabbing me for some reason.' Or, 'Production-wise, this doesn't fit into the format of radio right now.' Or some sort of practical thing. But it never is. 'Well, it's just not a single.' How can I correct that? 'Oh, well then I'll write some magical thing that will put you into a trance.' But having said that, sometimes I think it is magic. Sometimes I think they think it's magic. So they're waiting for magic."

She heaved a big sigh -- and then gathered steam. "But don't tell me it's not a single. A single is a record company's job: to pick out a song that they think is good and make sure people hear it. It's also incidentally, their job to come up with a way of selling records if, say, I don't have a single at all. What I still have is a great record with great songs." I asked Mann if she is ever tempted simply to give them what they want. "I've sort of tried to do it," she said. "I'll keep it in mind. I'll think, 'Well, this is pretty catchy' or 'I've kept this simple enough lyrically so that any moron can understand it.' But anytime I do that I get bored, and then I don't know how to finish the song. I really have to force myself to write and get into the studio, because this is the only career I have."

So, having resigned herself to the necessity of incanting some magic and delivering a single, one of the two songs that she is recording at Mad Dog today is called "Nothing Is Good Enough." Mann is known for writing clever, disappointed love songs that can also be read as damnations of the music industry. Lyrically and musically, they are sharp and subtle, angry and vulnerable. Her last solo record's title -- "I'm With Stupid" -- was a sardonic reference to her choice in both lovers and labels. "Nothing Is Good Enough," however, is a bit more direct. It's a song about defeat and the misery of delivering new material to an indifferent record executive.

"It doesn't really help that you can never say what you're looking for," she sings with aching sadness over a beautiful piano arrangement that brings to mind the classic pop of Burt Bacharach and Carole King. "But you'll know it when you hear it/know it when you see it/walk through the door/so you say, so you've said/many times before." It's a testament to her melodic gift and emotional phrasing that such a subject could sound so lovely, so memorable. It sounds -- could it be? -- like a single.

The next day, Mann, the session musicians and a producer, Buddy Judge, are back in the studio, and Judge, who worked on the song after Mann left the night before, plays a polished version of it. Mann is unhappy. She fears that the piano is too pretty, too "ballady," and sounds too much like another song on the album. "It's not the Moody Blues 70's flavor I was looking for," she says, slumped in a chair. "It's one thing to have a song be played as a gentle, sad ballad and another to be played as an '[Expletive] you,' which is what it's supposed to be. That anger can certainly be shown and be played. It's very hard for me to show it in the vocal, which never translates."

A decision is made to bring in a different drummer, and Mann tells the piano player to play his part as if he were "a drunken clown." Hausman suggests a "John Lennon, immature piano player" approach. While waiting for a new drummer, Dan MacCarroll, to arrive (he is also an A&R man at a small, independent label), Mann sits down with Hausman for a talk. "If this record doesn't sell," he says grimly, "Geffen's going to drop you." Mann, who calls Hausman, her former boyfriend, "Boo," sinks farther into her chair and says nothing. "I just want you to know the worst-case scenario and to begin to think about what you're going to do." Hausman -- ever the optimist -- throws out a few suggestions: go on a small acoustic tour! Start a new band! Play bass for someone else! "Goddamnit, Boo," Mann says with mock indignation. "Look at me. I can't even sit up. I don't even have the energy for good posture."

Before long, MacCarroll arrives. As Mann strums out the song for him on her bass guitar, MacCarroll says, "What beat do you want me to play it in?" She stares at him for a few seconds through her poker-straight, bleached white hair. "How about the hit-single beat?" she says, and they both snicker. "You're an A&R guy now. You know the hit-single beat." As she steps into the booth and puts on her headphones to record the song once more, she says into the microphone -- her dry, reedy voice now amplified through every speaker in the studio: "Whatever you do, don't ruin it for me. This is my last chance."

If this truly is Aimee mann's last chance, it will be a small tragedy. At 38, she is widely considered by her peers and music critics alike to be one of the finer songwriters of her generation. She has collaborated with Elvis Costello, Jules Shear and Chris Difford and Glenn Tilbrook of Squeeze -- all purveyors of the same kind of sophisticated pop music that gets little airplay these days. When alternative rock's perennial sweetheart, the singer-songwriter Liz Phair, met Mann backstage at a concert a few years ago, she knelt before her. Writing in Time magazine in 1996, David Thigpen called "I'm With Stupid" one of the "catchiest pop albums of the year, brimming with poised three-minute mini-masterpieces," and said that "Mann has the same skill that great tunesmiths like McCartney and Neil Young have: the knack for writing simple, beautiful, instantly engaging songs."

'Music has become just a soundtrack to the whole enterprise of celebrity. If Jackie O. could sort of carry a tune, she'd be perfect.' And yet she remains largely unrecognized by radio and the music-buying public. Bad timing, dumb luck and a rebellious attitude are partly to blame, but Mann's history of being mishandled by three different labels over a full decade reads like a cautionary tale about the struggle to be a serious recording artist in the contemporary music market. She carries with her the distinction of having had not one of her three solo albums released on the label it was recorded for, and the fate of her latest effort -- which Jim Barber, her A&R representative, says is Mann's best work yet -- is still up in the air. It's a sad, sorry tale that she is all too happy to spell out in her bittersweet songs. "You pay for the hands they're shaking/The speeches and the mistakes they're making/As they struggle with the undertaking of/Simple thought," she sings on a song from "I'm With Stupid." These digs at the label can be seen as brave, foolish or a little of both -- but they've certainly not helped her case.

Mann is not a complete stranger to fame and commercial success. One of the first songs she ever wrote by herself, "Voices Carry," went to No. 8 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1985, and the album went on to sell more than a million copies, and made her band, 'Til Tuesday, early MTV favorites at the height of New Wave. By the second and third 'Til Tuesday albums, Mann was flowering as a serious songwriter, and the synthesized dance-pop of the first album gave way to a more mature acoustic sound ("Strummy songs in D," Mann says), which did not go over well with either her label or her bandmates -- even as the acoustic sound of Suzanne Vega and Tracy Chapman was becoming popular.

Mann recorded three 'Til Tuesday albums for Epic Records in the 80's and then left the label after a rancorous battle over creative differences. It took her three years to get out of her contract, and all the while Epic wouldn't let her record elsewhere or release any new material. "That was the beginning of the funk," Hausman says, "the record-company roulette with contracts and lawyers. That really changed Aimee." Dick Wingate, who originally signed 'Til Tuesday to Epic and was the executive producer on "Voices Carry," quit the label after the first album, leaving Mann with no champion.

"She's the model of an artist who has been chewed up and spit out by the music business," Wingate says. "But Aimee herself is a pain. She's not a good people person. She's never really allowed herself to be close to anyone at any record label, including me. And the more bad luck and disappointment she had, the more distanced she became from the process."

In 1991, Mann released the material she had been working on for Epic as her first solo album, "Whatever," on Imago, a new independent label owned by Terry Ellis. Just as her second solo record was about to be released, Imago lost its distribution deal and financing and went into a tailspin; Ellis would neither release her album nor let her out of her contract for almost two years. Ellis finally sold the album to Geffen, which then signed Mann in 1994 and nearly a full year later released "I'm With Stupid."

In 1997, Mann married the singer-songwriter Michael Penn (Sean's older brother), another critics' darling who, like Mann, had a hit single, "No Myth," early in his career in 1990 and has since suffered through two labels botching his next two releases. (Penn has a new album due out in September from 57 Records, a division of Epic.) The couple have been keeping busy, though, cobbling together a new kind of middle-class rock career making music for films and performing Tuesday-night shows together at Largo, a sort of mellow rock supper club in West Hollywood. Since Largo opened two and a half years ago it has become the home for a group of wayward singer-songwriters, including Elliott Smith, Fiona Apple, Rufus Wainwright, Jon Brion, Grant Lee Phillips (of the band Grant Lee Buffalo) and the godmother of the underappreciated, Rickie Lee Jones. Their music can best be described as adult alternative pop. Put more simply, it's mature music. Jon Brion shot a pilot for VH1 that tries to transport the Largo vibe to TV, and some have suggested that Largo is the perfect model for the kind of smaller, focused record label that could lovingly and successfully break what the industry deems "difficult" artists like Mann.

Another comfort zone for both Mann and Penn has been the film industry. He has found work as a composer for the director Paul Thomas Anderson's movies, including "Boogie Nights" and "Hard Eight," while she has had songs on a dozen soundtracks in the past few years. Anderson, a Largo habitue and Fiona Apple's live-in boyfriend, has practically written his new film, "Magnolia," starring Tom Cruise, around eight Aimee Mann songs. "Simon and Garfunkel is to 'The Graduate,"' Anderson says, "as Aimee Mann is to 'Magnolia."'

Music artists stand to gain from the independent movement in the film industry. Elliott Smith's song "Miss Misery" appeared in Gus Van Zandt's "Good Will Hunting" and was nominated for an Academy Award. His performance on the Oscars in 1998 surely provided him with the largest audience he'll ever reach. Says Brion of Mann's work on "Magnolia," due out later this year, "That might be an alternative way of letting the world see that this is really a good batch of material."

It is, to put it mildly, a lousy time to be making popular music that's not aimed at teen-agers. On Dec. 10 last year, Seagram, which owned Universal Music Group, bought Polygram's musical holdings for $10.4 billion and collapsed the two organizations into one giant company -- which now accounts for 25 percent of the U.S. and European music markets. Honoring a promise to shareholders to unload assets and save $300 million a year, Seagram dismissed 3,000 employees and dropped some 200 artists from its rosters -- most of them album-oriented rock bands that have failed to thrive in today's teen-pop, singles-driven market. When the Seagram buyout was reported in The New York Times a few days before Christmas, the article was illustrated with a big picture of Mann, sinking into a couch, looking glamorously forlorn -- as good a visual representation as any of the despondency and uncertainty in the music industry.

In the merger, Mann's label, the alternative-rock-heavy Geffen -- founded as an artist-friendly oasis in the 70's by David Geffen and sold to Universal (then MCA) in 1990 -- was swallowed up by Interscope, a nine-year-old success story that has made most of its money from gangsta rap. Many artists and executives were on tenterhooks for weeks, waiting to hear whether they still had jobs or record deals. Jim Barber found out early on that he was moving to Interscope, but Mann, who presented her new album just after the news of the merger broke, remained a question mark through January. "It changes every day, and she's on this shifting line," Barber said then. "Aimee has been marketed as an alternative artist, and she's really a classic, straight-up singer-songwriter. Alternative rock isn't selling because alternative-rock bands aren't making records that anyone wants to buy. The reason all these bands are getting cut is because the labels hadn't totally dealt with that fact."

Says Jon Brion: "Everybody's talking about the implications of this whole Seagram's buyout, and in the near future they're terrible. But when it is made impossible for musicians to play for people who want to hear them, other systems develop. What a dumb thing for a record company to do when it's getting closer and closer to Internet trading for somebody without a major label becoming a reality. They're absolutely encouraging artists to be sovereign."

Brion has a point. With the example of artists like Ani DiFranco, who successfully started her own label, Righteous Babe, and the hotly contested MP3 technology, which allows listeners to download music from the Internet, artists suddenly have more motivation than ever to circumvent traditional -- some say soon-to-be-moribund -- means of distribution. Many artists believe that the industry's blindered focus on youth and singles will force their hands.

Nowhere has the shortsighted 60's manifesto "Don't trust anyone over 30" been taken more to heart than in the business of popular music. "People in my demographic aren't considered the juicy part of the record-buying public," says Gail Marowitz, 40, vice president of creative services at Sony Music (and Mann's personal art director and best girlfriend). "They think we're already old -- even though we buy plenty of records." Says Brion: "There's a whole culture for whom buying records -- new music -- is an important thing. That is a type of person."

Earlier this year, the Recording Industry Association of America released its annual consumer profile data for 1998, revealing a significant increase in music-buying by older women (the second year in a row that women bought more records than men) and a drop in purchases by consumers ages 10 to 29, with the worst slip among 20- to 24-year-olds, an age group that bought just half the records that the same age group did 10 years ago. The conclusion that many in the industry are drawing from these statistics is that young people today don't feel the need to own the music they listen to -- and that they're distracted by the Internet and video games. In other words, MTV and the radio will do just fine, thank you.

"There's an accepted wisdom that says, 'It's not a marketplace, don't market to people over 30,"' Mann says late one balmy night as we sit outside at an empty cafe on Melrose. "Well, who's buying all those Yanni records? Kids? From my perspective, record companies are looking for people who are almost freakishly multitalented, and music's the last on the list. People who are really attractive, so that they know how to model, because making videos and taking photographs is an enormous part of it. And you also have to be like an actor with an enormous capacity for schmoozing and talking to hundreds of people and making them like you, so there's a politician element to it. And you have to have an enormous amount of physical stamina to travel a lot and to be a big all-around entertainer, onstage and off. The music has become just a soundtrack to the whole enterprise of celebrity. If Jackie O. could sort of carry a tune, she'd be perfect."

Ladies and gentlemen/here's exhibit A:/didn't I try again?/and did the effort pay?/wouldn't a smarter Mann simply walk away?

-- "Nothing Is Good Enough," Aimee MannBack at Mad Dog Studios last July, Mann and I head outside to the parking lot and sit at a picnic table under the shade of an umbrella, sharing a cigarette. "I have to hammer out a new thing," she says softly. "Can I pretend having a record deal is the greatest thing on earth that will lead, automatically, to success, and people will love you for who you are? In no way can I do that. Knowing the enormous pitfalls of the music industry, I can't really pretend that anybody at a record company really believes in me or art at all. It's not their job to believe in art and me. I can't assume that anymore. And I really used to." She stops talking and stares out at the traffic, searching her inventory for the right words. "I think I've just learned from experience too well." She pauses for an unbearably long time and looks as if she is about to cry. "I don't believe in it anymore. I think I just gave up the dream. And the dream was not to be rich and famous or sell a lot of records. The dream was that I would work with people and they would be helpful, and if I was having a tough time, they would be understanding and we'd all sort of work together. But that doesn't happen, and I don't believe it ever will. It's so distasteful to me, the idea that I could once again go on tour and feel like a constant disappointment. And you are a constant disappointment. If you're not really on top of it and you want it so bad that you'll make love to everybody that comes near you -- those kind of people aren't disappointing. Their fans are people who meet them and say, 'What a great guy Garth Brooks is!' He's got a limitless hunger that translates into success. It's an ability that I just don't have. I'm tired of feeling like a loser in that respect." Another long pause. "Musically, I don't feel like a loser at all."

The riddle of Mann's existence is that she wants respect from an industry that only rewards respect -- and artistic freedom -- to those who make it a lot of money. Warner Brothers surely did not tell Madonna, "We don't hear a single," when she turned in her last album -- one that sounded like nothing on the radio. Setting out to write hit singles carries with it the not-so-hidden danger of selling out -- and, consequently, the potential loss of critical respect. "There's a fine line," Mann says, "between singles and jingles."

It's more than a little odd that just a few hours after Mann told me that she "gave up the dream," she went back into the studio and recorded a song called "Red Vines" that Jim Barber said he believed was, at long last, magic. "I think 'Red Vines' is a hit," he said to me in January. Of course, he also had to deal with the sting of "Nothing Is Good Enough," a song he felt was aimed directly at him. "I take offense to that line 'You'll know it when you hear it walk through the door,"' he said. "I was way more specific than that. I said to her: 'Aimee, this is why your choruses aren't working. This is the kind of chorus you should write.' I made her this tape once of songs that I think have good choruses."

By late January, Mann is "a changed person," according to Hausman. Though the news of her getting picked up by Interscope kind of trickled in -- no big call from the boss saying, "Welcome aboard" -- she is happy that things are moving forward. She has presented a dozen songs for an album that she plans to call "Bachelor No. 2." She is told that everyone loves it. One day in January, I get an E-mail from her in which she jokingly refers to the new "positive me." The songs "sound great," she writes. "For the first time, I'm actually excited about my own record."

'I've suddenly realized that if I have one song that they think is a single, they really don't care about the rest of the record. Then I can make the rest of the record good.' Gail Marowitz explains: "Basically, I think she's coming to a point in her career where it goes down a little easier to play by the rules than it used to. When we were discussing her album packaging a couple of weeks ago, I said to her, 'O.K., Aimee, come on, be honest with me -- you wanna sell records?' And I hear this dead silence. And I'm, like: 'Come on, Aim, come on. Whaddaya think?' And she says, quietly: 'Yeah ... yeah. I wanna sell records.' And I'm, like: 'Good. Good. That's the first step."'

One morning in January, Mann says over the phone: "I've had this revelation about singles. I've suddenly realized that if I have one song that they think is a single, they really don't care about the rest of the record. Then I can make the rest of the record good. This is my new philosophy -- I actually want to be a one-hit wonder. It's only to my benefit."

And the good news keeps coming. She is asked to join this summer's Lilith Fair, in the coveted slot of closing act on the second stage. Then, on March 22, she has a big meeting with the three principals at Interscope -- Jimmy Iovine, Ted Fields and Tom Whalley -- plus Barber to discuss her album and, she thinks, a marketing strategy. Hausman, who lives in New York, flies out for the meeting, and Mann, buoyant, actually looks forward to it. Iovine is late, so the others start without him, telling Mann that they love her record, and begin discussing its release. But when Iovine finally arrives, a red flag goes up. He hasn't listened to the record, but says, "The record's not done until it's done," and suggests that she write some more songs. Iovine tells Mann he'll listen to it and call her in two days. He never calls.

After five days, Mann contacts Iovine's office, only to discover that he has gone on vacation for two weeks. He does not call her while he is away, nor when he returns. It is now mid-April, three weeks after Iovine said he would call in two days. Mann is enraged. "The problem is, I'm not hearing nothing because they love it," she says. "When I finally hear from them, it's going to be something like, 'We really think you need to rerecord four songs.' So I'm waiting for bad news. I just don't know how bad the news is. I'm two inches away from saying: 'Keep the record. I've had it. I'll make another one at home, and I'll be shed of you people once and for all."'

What's most troubling to Mann is that it's now almost too late for her album to be released in time to go on tour with Lilith Fair. "Their vast indifference is costing me my career," she says. "I started recording this album two years ago. So it would be a three-year-long project, four years since my last record to come out, when I was waiting for people to care. They're never going to care. They're never going to have that excitement about me as they do about the new Britney Spears. They consider Beck or Alanis Morisette edgy and risk-taking, which is crazy, because they sell millions of records. Jewel is way out there on the edge! That's what I've come into. It's the new legacy."

By the next day, the truth -- the bad news -- finally comes. "They don't like the record," she tells me. "This is actually the worst it's ever been for me. Iovine actually said to someone: 'Aimee doesn't expect us to put this record out as it is, does she? If Aimee just wants to put out a record for her fans, this is not the place to do it.' It's so disingenuous, because they're trying to position it like: 'Doesn't Aimee want to be a big star? Because that's what it will take.' Yeah, you know, I've decided not to be a big star. I've decided I can't handle success. I'm doing this because I wanted to be my own boss, because I couldn't take orders from people. And all I get are more orders about something that can't be ordered around: go write a hit song."

True to form, Mann sums up with a relationship analogy: "Part of the problem was 'Magnolia' -- that Paul Thomas Anderson was so interested in me. It raised my profile enough for them to go: 'Hey, maybe we shouldn't break up with our girlfriend. Look at all the guys checking her out.' But it didn't make him love her any more. It's the same rotten relationship it always was. It just made him hold on a little tighter."

By the following week, Mann is beginning to feel a bit more sanguine about her situation. And she is finally taking steps toward doing something she probably should have done long ago: becoming sovereign. Her lawyers are negotiating a price to buy back her master recordings from Interscope. Hausman has hired someone to build a Web site. And he and Mann are exploring the possibilities of starting their own label. Mann would like to call it Superego Records. "If Aimee sold 70,000 records independently," Marowitz says, "she would be making more money than if she sold 300,000 on a major label. And Aimee's good for 70,000, and she'll get major distribution. Ultimately, it's a very good thing." And then more good news: Hausman gets a call from Dick Wingate, who is now the vice president of content development at Liquid Audio, the only Internet music company thus far to be endorsed by the Recording Industry Association of America. (In April, Liquid Audio enabled the first-ever promotional download of music on Amazon.com.) Wingate, who hadn't talked to Mann in years, remained a fan. "This technology should encourage disenfranchised artists like Aimee," he says. "The Internet allows artists to distribute their music the moment it's done if they want to and not have to wait for the typical cycle that a record company requires. Artists want to communicate directly with their fans." Indeed, Liquid Audio is only one of several companies competing for primacy on the Internet. Alanis Morisette has become a partner in MP3.com, while Microsoft and AT&T are weighing in with their own formats. The paradigm is shifting.

In June, Mann gets booked on four Lilith Fair dates in early August: Buffalo, Boston, Hartford and Jones Beach -- and says that there may even be a record for sale by then. "I'm feeling good," she says of her newfound independence, "because I'm tapped into something that I'm more suited to." The decadelong major-label nightmare is finally ending. As is her way, Mann turns to a metaphor to describe how she feels: "I really picture somebody sitting in front of a big book and getting totally fed up and slamming it shut, and a big puff of dust comes up from it," she says, laughing. "I can read no farther. I don't want to know how this book ends. I hate this guy's writing. It's over." She laughs again, not yet knowing if it's the last laugh. She knows this much, though: "I'm never going to open that book again."

Photograph by George Lange

Nothing is good enough: With Penn at Largo, where wayward artists find homey comfort. Photograph by Andrew MacNaughtan

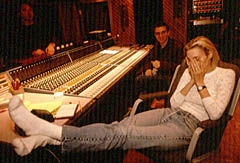

She's not with stupid: Hausmann, former boyfriend and current manager, can appreciate her sardonic double references to lovers and labels. Photograph by Lauren Greenfield

Whatever: Many have botched a career that looked so promising in 'Til Tuesday days. Photograph by Lisa Siefert